WBBSE Solutions For Class 10 Maths Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Similar Objects

We see infinite number of objects in our daily life. There exists many similarities among these objects.

Again, sometimes there exists no similarity between them. The size and shape of some objects are likely to be the same. These objects are said similar objects.

Definition of similar objects

If two objects be of same shape though their sizes may or may not be the same, then the objects are called similar objects.

WBBSE Solutions for Class 10 Maths

For example, all squares (whatever their sizes may be ) are similar, all circles are similar, all equilateral triangles are similar.

The squares ABCD and PQRS are similar, The circles with centres A and B are similar and the equilateral triangles ΔABC and ΔPQR are also similar.

Thus, if the shapes of two or more than two objects, although their sizes may or may not be the same, then they can be said to be similar objects.

Equiangular triangles

Three angles of two or more than two triangles may or may not be equal.

If they are equal, then we call them equiangular triangles. For example, the three angles of the triangles ABC and PQR are equal, i,e., ∠A = ∠P, ∠B = ∠Q and ∠C = ∠R.

So the triangles are equiangular.

Definition

If the three angles of a triangle are equal to the three angles of another triangle, then the two triangles are called equiangular triangles.

Obviously in other words we can say that if any two amgles of a triangles be equal to any two angles A of another triangle, then the two triangles are called equiangular triangles.

Since in this case, the rest third angle of the two triangles are always equal.

The sizes of equiangular triangles may be different even though the shapes of them are similar.

So, one of the two equiangular triangles may be called increased or decreased form of the another triangle, i.e, if a triangle is increased or decreased by its size, then it will be always equiangular to the previous triangle.

For example, ΔABC is the increased form, of ΔPQR and conversely ΔPQR is the decreased form of ΔABC.

In both the cases, the triangles are equiangular.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Similar Triangles

Definition

If two or more than two triangles be equiangular and the ratios of their corresponding sides be equal, then the triangles are called similar triangles.

i,e., if ΔABC and ΔDEF be similar triangles, then ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E and ∠C = ∠F and \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}=\frac{\mathrm{CA}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

Axioms of similarity of triangles

Axiom 1: If the ratios of the three pair of corresponding sides are equal, then the two triangles are similar to each other.

It is called S-S-S similarities of two triangles.

Axiom 2: If two angles of a triangle are equal to two angles of another triangle, then the triangles are similar to each other.

It is called angle-angle (A – A) similarity.

Axiom 3: If one pair of angles of two triangles are equal and their adjacent sides arc proportionate, then the triangles are similar to each other.

It is called S-A-S similarity.

The shape of two similar triangles are same, even though their sizes may or may not be the same.

Congruent triangles

If two or more than two triangles are equal in all respects, then the triangles are called congruent triangles.

For example, both the shapes and sizes of two triangles ΔABC and ΔPQR are equal.

So, they are congruent triangles.

Definition

If the shapes and sizes of two or more than two triangles be the same, then they are called congruent triangles.

For example, the shapes and sizes of ΔABC and ΔPQR are equal.

Hence they are congruent triangles.

Sign of similarity and congruency

The sign “∼” is known as the sign of similarity.

Such as, if the triangles ΔABC and ΔPQR are similar, then we write ΔABC ∼ ΔPQR which means that ΔABC and ΔPQR are similar.

ΔABC ∼ ΔPQR, i.e., ΔABC and ΔPQR are similar to each other.

Because, ∠A = ∠P, ∠B = ∠Q, and ∠C = ∠R, But AB ≠ PQ, BC ≠ QR, and AC ≠ PR, even though \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{PR}}\).

In ΔABC = ΔPQR i.e., ΔABC and ΔPQR are congruent to each other; since, ∠A = ∠P, ∠B = ∠Q, and ∠C = ∠R and the corresponding sides AB = PQ, BC = QR, and AC = PR.

[Note: The areas of two similar triangles may or may not be equal. But the areas of two bcongruent triangles are always equal.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Conditions Of Congruency

Condition 1. If three sides of any triangle be equal to the corresponding three sides of another triangle, then the triangles are congruent. It is called the S-S-S condition of congruency.

Condition 2. If any two sides of a triangle and their included angle be equal to two sides of another, triangle, then the two triangles are congruent to each other.

Condition 3. If two angles and one Side of a triangle be equal to the two angles and the corresponding side of another triangle, then the triangles are congruent to each other. It is called the A-A-S condition of congruency.

Condition 4. If the hypotenuse and any other side of a right-angled traiangle be equal to the hypotenuse and the corresponding side of another right-angled triangle, then the triangles are congruent to each other.

It is called the R-H-S condition of congruency.

If two triangles satisfies and obey any one ot the above four conditions, then the triangles are called congruent triangles.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Thales Theorems

Thales was a famous mathematician and philosopher of ancient Greece.

He used an important theorem regarding equiangular mangles’. The theorem was :“The corresponding sides of two equiangular triangles are proportionate.”

We shall now state and prove Thale’s theorem.

Thales’ Theorem:

Statement: A straight line parallel to any side of any triangle divides other two sides (or the extended two sides) proportionally.

Proof: Let in ΔABC, the straight line DE parallel to BC intersects the sides AB and AC at the points D and E respectively and extended AB and AC in the points D and E respectively.

To prove: AD: BD = AE; CE

Construction: Let us join B, E and C, D.

Proof: ΔBED and ΔCED lie on the same base DE and between same parallels DE and BC.

∴ areas of the triangles of ΔBED and ΔCED are equal, i.e, area of ΔBED = area of ΔCED.

or, \(\frac{1}{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{BED}}=\frac{1}{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{CED}}\)

or, \(\frac{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{BED}}=\frac{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{CED}}\)

But AD and BD are the bases of ΔADE and ΔBED and lie on the same straight line and their vertices are the same point E.

So, the heights of the triangles are equal.

We know that the ratio of the areas of triangles having same heights is equal to the ratio of their bases.

∴ \(\frac{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{BED}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}\)…..(1)

Similarly, it can be proved that

\(\frac{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{BED}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)….(2)

So, from (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

or, AD : BD = AE : CE

Hence AD : BD = AE : CE (Proved)

[Note: This theorem is also known as theorem of basic proportionality.]

We shall now prove logically the converse theorem of Thales’ theorem by the method of geometry.

Converse Of Thales’ Theorem

Statement: If a straight line divides any two sides (or their extended sides) in the same ratio, it will be parallel to the third side.

Given: Let the straight line DE divides two sides AB and AC of ΔABC (or the extended AB and AC) in equal proportion, i.e.,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

To prove DE || BC.

Construction: Let us join B, E and C, D.

Proof: The bases AD and BD of ΔADE and ΔBDE lie on the same straight line and their common vertex is E.

∴ the heights of the triangles are equal.

∴ the ratio of the areas of the triangles is equal to the ratio of their bases.

\(\quad \frac{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{BED}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}\)…..(1)

Similarly, it can be proved that

\(\frac{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{CED}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)….(2)

But given that \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

∴ \(\quad \frac{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{BED}}=\frac{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \triangle \mathrm{CED}}\)

or, area of ΔBED = area of ΔCED.

But the two ΔBED and ΔCED of equal areas lie on the same base DE and on the same side of DE.

So, the triangles lie between the same pair of parallel straight lines DE and BC.

Hence DE || BC. (Proved) .

“WBBSE Class 10 similarity solved examples”

Corollary 1. The straight line parallel to side BC of ΔABC intersects the sides AB and AC at points D and E respectively. Prove that

1. \(\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{A C}{C E}\)

Proof: From Thale’s theorem we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{A D}}{\mathbf{B D}}=\frac{\mathrm{A E}}{\mathrm{C E}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}+1=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}+1\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}+\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}+\mathrm{CE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{CE}}\) (proved)

2. \(\frac{\mathrm{A D}}{\mathrm{A B}}=\frac{\mathrm{A E}}{\mathrm{A C}}\)

Proof: From Thale’s theorem we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{A D}}{\mathbf{B D}}=\frac{\mathrm{A E}}{\mathrm{C E}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{CE}}{\mathrm{AE}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{AD}}+1=\frac{\mathrm{CE}}{\mathrm{AE}}+1\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}+\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{CE}+\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{AE}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AE}}\)

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AE}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{AC}}\)(Proved)

Corollary 2. The line segment joining the mid-points of any two sides of a triangle is parallel to the third side of the triangle.

Solution: Let D and E be the mid-points of the sides AB and AC of a ΔABC.

To prove DE || BC.

Construction: Let us join B, E and C, D.

Proof: ΔADE = \(\frac{1}{2}\) x AD x h…….(1), where h = distance of AD from E = height of ΔADE.

Again, ΔBED = \(\frac{1}{2}\) x BD x h= \(\frac{1}{2}\) x AD x h…….(2), [AD = BD]

[Here the value of h in both cases will be the same.]

∴ from (1) and (2) we get, ΔADE = ΔBED ……..(3)

Similarly, it can be proved that ΔADE = ΔCED ……… (4)

From (3) and (4) we get, ΔBED = ΔCED.

But these are on the same base DE and on the same side of DE.

So, the triangles will lie between the same parallels.

∴ DE || BC. (Proved)

“Similarity theorems for Class 10 Maths”

Corollary 3. Prove that the internal or external bisector of any angle of a triangle divides its opposite side in the ratio of the lengths of the adjacent sides of the angle internally or externally.

Solution: AD is the internal bisector of ∠BAC or external bisector which intersects BC or extended BC of ΔABC at the point D.

To prove: BD: DC = AB: AC

Construction: Let us draw a straight line through C parallel to DA which intersects BA and extended BA at a point E.

Proof: DA || CE [by construction], ∴ ∠DAC = alternate ∠ACE.

Again, DA || CE, ∴ ∠BAD (or, ∠FAD) = similar ∠AEC.

But ∠BAD (or ∠FAD) = ∠DAC.

∴ ∠ACE = ∠AEC. ∴ AC = AE

Now, in ΔBEC or in ΔBDA

DA || CE; So, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{DC}}=\frac{\mathrm{BA}}{\mathrm{AE}}\) [by Thales’ theorem]

i.e., BD : DC = AB : AE

or, BD : DC = AB : AC [AE = AC]

∴ BD: DC = AB: AC (Proved)

In the following examples how the above theorems are applied to solve the real problems is discussed thoroughly.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity Multiple Choice Questions

“Chapter 5 similarity exercises WBBSE solutions”

Example 1. A line parallel to the side BC of ΔABC intersects the sides AB and AC at the points X and Y respectively. If AX = 2.4 cm, AY = 3.2 cm, and YC = 4.8 cm, then the length of AB is

- 3.6 cm

- 6 cm

- 6.4 cm

- 7.2 cm

Solution:

Given

A line parallel to the side BC of ΔABC intersects the sides AB and AC at the points X and Y respectively. If AX = 2.4 cm, AY = 3.2 cm, and YC = 4.8 cm

The side BC of ΔABC is parallel to XY and XY intersects AB and AC at X and Y respectively.

∴ by Thales’ theorem,

\(\frac{A X}{B X}=\frac{A Y}{C Y}\)

or, \(\frac{B X}{A X}=\frac{C Y}{A Y}\)

or, \(\frac{B X+A X}{A X}=\frac{C Y+A Y}{A Y}\)

or, \(\frac{A B}{2 \cdot 4}=\frac{4 \cdot 8+3 \cdot 2}{3 \cdot 2}\)

[AX = 2.4 cm, AY = 3.2 cm and CY = 4.8 cm]

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{2 \cdot 4}=\frac{8}{3 \cdot 2}\)

or, AB=\(\frac{8 \times 2 \cdot 4}{3 \cdot 2}=6\)

∴ AB = 6 cm

∴ 2. 6 cm is correct

Example 2. The point D and E are situated on the sides AB and AC of ΔABC in such a way that DE || BC and AD : DB = 3 : 1; If EA = 3.3 cm, then the length of AC is

- 1.1 cm

- 4 cm

- 4.4 cm

- 5.5 cm

Solution:

Given

The point D and E are situated on the sides AB and AC of ΔABC in such a way that DE || BC and AD : DB = 3 : 1; If EA = 3.3 cm

In ΔABC, DE || BC,

∴ by Thales’ theorem, we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{CE}}{\mathrm{AE}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}+\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{CE}+\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{AE}}\)

or, \(\frac{4}{3}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{3 \cdot 3}\)

[AD: DB=3 :1 or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{1}{3}\)

or, 3AC=4 x 3.3

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}+\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{3+1}{3}=\frac{4}{3}\)]

or, AC =\(\frac{4 \times 3 \cdot 3}{3}\)

or, AC = 4. 4

∴ AC = 4.4 cm

∴ 3. 4.4 cm is correct

“Class 10 Maths properties of similar triangles”

Example 3. If DE || BC, then the value of x is

- 4

- 1

- 3

- 2

Solution: In ΔABC, DE || BC

∴ by Thales’ theorem, we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}+\mathrm{BD}}\) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AE}+\mathrm{CE}}\)

or, \(\frac{x+3}{3 x+19}\) = \(\frac{x}{3 x+4}\)

or, 3x2 + + 4x + 9x+ 12 = 3x2 + 19x

or, 3x2 + 13x – 3x2 -19x + 12 = 0

or, -6x + 12 = 0 or, 6x = 12 or, x = \(\frac{12}{6}\)

Hence the required value of x is 2

∴ 4. 2 is correct

Example 4. In the trapezium ABCD, AB || DC and the two points P and Q are situated on the sides AD and BC in such a way that PQ || DC; if PD = 18 cm, BQ = 35 cm, QC = 15 cm, then the length of AD is

- 60 cm

- 30 cm

- 12 cm

- 15 cm

Solution:

Given

In the trapezium ABCD, AB || DC and the two points P and Q are situated on the sides AD and BC in such a way that PQ || DC; if PD = 18 cm, BQ = 35 cm, QC = 15 cm,

In trapezium ABCD, AB || DC.

Construction: The sides DA and CB of the trapezium are extended.

Let extended DA and extended CB intersect at the point x.

Now, in ΔXPQ, AB || PQ [PQ || DC and AB || DC

∴ by Thales Theorem, \(\frac{X A}{A P}=\frac{X B}{B Q}\)

or, \(\frac{X A}{X B}=\frac{A P}{B Q}\)……(1)

Again, in ΔXCD, AB || DC

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{X A}{A D}=\frac{X B}{B C}\)

or, \(\frac{X A}{X B}=\frac{A D}{B C}\) ……(2)

From (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{A P}{B Q}=\frac{A D}{B C}\)

or, \(\frac{A D-P D}{B Q}=\frac{A D}{B Q+C Q} \text { or. } \frac{A D-18}{35}=\frac{A D}{35+15}\)

[PD = 18 cm, BQ = 35 cm and CQ = 15 cm]

or, \(\frac{A D-18}{35}=\frac{A D}{50}\)

or, 50 AD – 900 = 35 AD

or, 15 AD = 900 or, AD = \(\frac{900}{15}\) = 60

∴ AD = 60

∴ 1. 60 cm is correct

Example 5. If DP = 5 cm, DE = 15 cm, DQ = 6 cm and QF = 18 cm, then

- PQ = EF

- PQ || EF

- PQ ≠ EF

- PQ ∦ EF.

Solution:

Given

If DP = 5 cm, DE = 15 cm, DQ = 6 cm and QF = 18 cm

We know, 15 cm = \(\frac{5 \mathrm{~cm}}{15 \mathrm{~cm}}\) = \(\frac{1}{3}\)

and \(\frac{6 \mathrm{~cm}}{18 \mathrm{~cm}}\) = \(\frac{1}{3}\)

∴ \(\frac{5 \mathrm{~cm}}{15 \mathrm{~cm}}=\frac{6 \mathrm{~cm}}{18 \mathrm{~cm}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{DQ}}{\mathrm{QF}}\),

i.e.. in ΔDEF, \(\frac{\mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{DQ}}{\mathrm{QF}}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{PE}} \neq \frac{\mathrm{DQ}}{\mathrm{QF}}\)

∴ by the converse of Thales’ theorem,

∴ PQ ∦EF

∴ 4. PQ ∦EF is correct.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity True Or False

Example 1. Two similar triangles are always congruent.

Solution: False, since the angles of two similar triangles are equal, even though their sides are not equal, but proportionate.

Example 2. In the adjoining If DE || BC, then \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

Solution: True, since DE || BC

∴ by Thales theorem \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}\)

or, \(\frac{A D+B D}{B D}=\frac{A E+C E}{C E}\) or, \(\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{A C}{C E}\)

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity Fill In The Blanks

Example 1. The line segment parallel to any side of a triangle divides other two sides or the extended two sides ______

Solution: Proportional

Example 2. If the bases of two triangles are situated on a same line and other vertex of the two triangles are common, then the ratio of the areas of two triangles are ______ to the ratio of their baes.

Solution: Equal

Example 3. The straight line parallel to the parallel sides of a trapezium divides ______ others two sides.

Solution: Proportional

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity Short Answer Type Questions

“Understanding similarity in geometry for Class 10”

Example 1. If in ΔABC, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EC}}\) and if ∠ADE = ∠ACB, then write what type of triangle according to side ΔABC is?

Solution:

Given:

If in ΔABC, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EC}}\) and if ∠ADE = ∠ACB

In ΔABC, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EC}}\)

∴ by the converse of Thales’ theorem DE || DC.

∴ ∠ADE = similar ∠ABC

or, ∠ACB = ∠ABC [Given that ∠ADE = ∠ACB]

∴ AB = AC, ∴ ΔABC is an isosceles triangle.

Example 2. In DE || and if AD : BD = 3: 5, then find (area of ΔADE) : (area of ΔCDE).

Solution:

Given:

In DE || and if AD : BD = 3: 5

In ΔABC, DE || BC,

∴ by Thales’ theorem,

\(\frac{A D}{B D}=\frac{A E}{C E}\) …….(1)

Also given that AD : BD = 3 : 5 or, \(\frac{A D}{B D}=\frac{A E}{C E}\) = \(\frac{3}{5}\)

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}=\frac{3}{5}\)

Now, AE and CE lie on the same straight line and D is the common vertex of ΔADE and ΔCDE,

∴ the heights of both triangles are the same. Let the equal heights be h.

∴ \(\frac{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{ADE}}{\text { area of } \Delta \mathrm{CDE}}=\frac{\frac{1}{2} \times \mathrm{AE} \times h}{\frac{1}{2} \times \mathrm{CE} \times h}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CE}}=\frac{3}{5}\) [from{2}]

Hence the required ratio is 3: 5.

Example 3. The LM || AB and if AL = (x – 3) unit, AC = 2x unit, BM = (x-2) unit and BC = (2x + 3) unit, then find the value of x.

Solution:

Given:

The LM || AB and if AL = (x – 3) unit, AC = 2x unit, BM = (x-2) unit and BC = (2x + 3) unit

In ΔABC, LM || AB.

∴ by Thales theorem, \(\frac{C L}{A L}=\frac{C M}{B M}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{CL}+\mathrm{AL}}{\mathrm{AL}}=\frac{\mathrm{CM}+\mathrm{BM}}{\mathrm{BM}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AL}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{BM}}\)

or, 2x2 – 4x = 2x2 – 6x + 3x – 9 or, – 4x = – 3x – 9

or, – x = – 9 or, x = 9

Hence the required value of x = 9

Example 4. If in ΔABC, DE || PQ || BC and AD = 3 cm, DP = x cm, PB = 4 cm, AE = 4 cm, EQ = 5 cm, QC = y cm, then determine the value of x and y

Solution:

Given:

If in ΔABC, DE || PQ || BC and AD = 3 cm, DP = x cm, PB = 4 cm, AE = 4 cm, EQ = 5 cm, QC = y cm

In ΔAPQ, DE || PQ,

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{3 \mathrm{~cm}}{x \mathrm{~cm}}=\frac{4 \mathrm{~cm}}{5 \mathrm{~cm}}\)

[AD =3 cm, DP = x cm, AE = 4 cm and EQ = 5 cm]

or, \(\frac{3}{x}=\frac{4}{5}\) or, 4 x=15 or, \(x=\frac{15}{4}\)

Again, in ΔABC, PQ || BC, ∴ by Thales’ theorem

\(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{PB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{QC}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}+\mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{PB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}+\mathrm{EQ}}{\mathrm{QC}}\)

or, \(\frac{3 \mathrm{~cm}+x \mathrm{~cm}}{4 \mathrm{~cm}}=\frac{4 \mathrm{~cm}+5 \mathrm{~cm}}{y \mathrm{~cm}}\)

or, \(\frac{3+x}{4}=\frac{9}{y}\)

or, \(\frac{3+\frac{15}{4}}{4}=\frac{9}{y}\)

[because x = \(\frac{15}{4}\)]

or, \(\frac{27}{16}=\frac{9}{y}\) or, 3 y=16

or, y = \(\frac{16}{3}\)

Hence the required value of x = \(\frac{15}{4}\) and y= \(\frac{16}{3}\)

Example 5. In the adjoining, if DE || BC, BE || XC and \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{2}{1}\) then value of \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}\)

Solution:

Given:

In the adjoining, if DE || BC, BE || XC and \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{2}{1}\)

In ΔABC, DE || BC,

∴ by Thales’ theorem,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EC}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EC}}=\frac{2}{1}\) [because \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DB}}=\frac{2}{1}\)]

or, AE = 2EC …..(1)

Again, in ΔAXC, BE || XC,

∴ by Thales’ Theorem,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BX}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{EC}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{XB}}=\frac{2 \mathrm{EC}}{\mathrm{EC}}\)[from (1)]

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{XB}}=2\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{XB}}=\frac{2}{1}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}+\mathrm{XB}}{\mathrm{XB}}=\frac{2+1}{1}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AX}}{\mathrm{XB}}=\frac{3}{1}\),

∴ the value of \(\frac{\mathrm{AX}}{\mathrm{XB}}\) is \(\frac{3}{1}\).

Example 6. Write the correct answer

1. All squares are  (congruent/similar)

(congruent/similar)

Solution: Similar

2. All squares are  (congruent/similar)

(congruent/similar)

Solution: Similar

3. All  (equilateral/isosceles) triangles are always similar.

(equilateral/isosceles) triangles are always similar.

Solution: Equilateral

4. Two quadrilaterals will be similar if their similar angles are  (equal/proportional) and similar sides are

(equal/proportional) and similar sides are  (unequal/proportional)

(unequal/proportional)

Solution: Equal, Proportional

Example 7. Write whether the following statements are true or false

1. Any two congruent are similar.

Solution: True

2. Any two similar are always congruent.

Solution: False

3. The corresponding angles of any two polygonal are equal.

Solution: True

4. The corresponding sides of any two polygonal are proportional.

Solution: True

5. The square and rhombus are always similar.

Solution: False

Example 8. Write an example of a pair of similar images.

Solution: A pair of similar figures is two circles of unequal diameter as shown.

Example 9. Construct a pair of dissimilar images.

Solution: The Images are not similar.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity Long Answer Type Questions

Example 1. A line parallel to the side BC of AABC intersects the sides AB and AC at points P and Q respectively.

1. If PB = AQ, AP = 9 units, QC = 4 units, then calculate the length of PB.

2. The length of PB is twice of AP and the length of QC is 3 units more than the length of AQ, then calculate the length of AC.

3. If AP = QC, the length of AB is 12 units and the length of AQ is 2 units, then calculate the length of CQ.

Solution:

1. In ΔABC, PQ || BC.

∴ by Thales’ theorem \(\frac{A P}{B P}=\frac{A Q}{C Q}\) …….(1)

or, \(\frac{9}{\mathrm{AQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{4}\)

[ because AP = 9 units, QC = 4 units]

or, AQ2 = 36 or, AQ = √36 or, AQ = 6

∴ from (1) we get, \(\frac{9}{P B}=\frac{6}{4}\)

∴ the length of PB = 6 units.

2. From (1) of ΔABC, PQ || BC we get, \(\frac{A P}{B P}=\frac{A Q}{C Q}\)

or, \(\frac{A P}{2 A P}=\frac{A Q}{A Q+3}\) [as per question]

or, \(\frac{1}{2}\) = \(\frac{A P}{2 A P}=\frac{A Q}{A Q+3}\)

or, 2AQ = AQ + 3

or, AQ = 3

∴ QC = AQ + 3 = (3 + 3) units = 6 units.

∴ AC = AQ + QC = (3 + 6) units = 9 units.

∴ the length of AC = 9 units.

3. From (1) of ΔABC, PQ || BC we get, \(\frac{A P}{B P}=\frac{A Q}{C Q}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AP}+\mathrm{BP}}{\mathrm{BP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}+\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PB}}=\frac{2+\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{12}{\mathrm{~PB}}=\frac{2+\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)………(2)

Again, \(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{BP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{BP}}=\frac{2}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

or, 2 PB= CQ2

or, PB= \(\frac{\mathrm{CQ}^2}{2}\)

From (2) we get, \(\frac{12}{\frac{\mathrm{CQ}^2}{2}}=\frac{2+\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{24}{\mathrm{CQ}^2}=\frac{2+\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{24}{\mathrm{CQ}}=2+\mathrm{CQ}\) [because \(\mathrm{CQ} \neq 0\)]

or, 2CQ + CQ2 = 24 or, CQ2 + 2CQ – 24 = 0 or, CQ2 + 6CQ – 4CQ – 24 = 0

or, CQ (CQ + 6) – 4 (CQ + 6) = 0 or, (CQ + 6) (CQ – 4) = 0

either CQ + 6 = 0 or, CQ – 4 = 0

⇒ CQ = – 6 ⇒ CQ = 4

But the value of CQ cannot be negative.

∴ CQ = 4 units.

∴ the required length of CQ = 4 units

Example 2. X and Y are two points on the sides PQ and PR respectively of the ΔPQR.

1. If PX = 2 units, XQ = 3.5 units, YR = 7 units, and PY = 4.25 units, then find whether XY and QR are parallel or not.

2. If PQ = 8 units, YR =12 units, PY = 4 units and the length of PY is 2 units less than that of XQ, then find whether XY and QR are parallel or not.

Solution:

1. In ΔPQR, XY and QR will be parallel if \(\frac{\mathrm{PX}}{\mathrm{QX}}=\frac{\mathrm{PY}}{\mathrm{RY}}\)

Now, \(\frac{P X}{Q X}=\frac{2 \text { units }}{3: 5 \text { units }}=\frac{2}{\frac{35}{10}}=\frac{4}{7}\)

Again, \(\frac{P Y}{R Y}=\frac{4 \cdot 25 \text { units }}{7 \text { units }}=\frac{17}{28}\)

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{PX}}{\mathrm{QX}} \neq \frac{\mathrm{PY}}{\mathrm{RY}}\)

∴ \(\mathrm{XY}||\mathrm{QR}\)

2. In ΔPQR, XY and QR will be parallel if \(\frac{\mathrm{PX}}{\mathrm{QX}}=\frac{\mathrm{PY}}{\mathrm{RY}}\) …….(1)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{PX}+\mathrm{QX}}{\mathrm{QX}}=\frac{\mathrm{PY}+\mathrm{RY}}{\mathrm{RY}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{PQ}}{\mathrm{QX}}=\frac{4+12}{12}\)

or, \(\frac{8}{6}=\frac{16}{12}\) [because QX = PY + 2 = 4 + 2 = 6]

or, \(\frac{4}{3}=\frac{4}{3}\)

∴ \( \frac{\mathrm{PX}}{\mathrm{QX}}=\frac{\mathrm{PY}}{\mathrm{RY}}\)

∴ XY || QR.

Hence according to the given conditions XY and QR are parallel.

Example 3. With the help of Thales’ theorem prove that the line drawn through the mid-point of one side of a triangle parallel to another side bisects the third side.

Solution:

Let the mid-point of AB of the ΔABC be E and a straight line EF passing through E and parallel to BC which intersects AC at point F.

To prove: F is the mid-point of AC, i.e., AF = CF.

Proof: In ΔABC, EF || BC. (Given).

∴ by Thales’ theorem we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{BE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AF}}{\mathrm{CF}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{AE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AF}}{\mathrm{CF}}\)

or, \(1=\frac{\mathrm{AF}}{\mathrm{CF}}\)

or, AF = CF

Hence F is the mid-point of AC, i.e., EF has bisected AC (Proved)

Example 4. In ΔABC, P is a point on the median AD. Extended BP and CP intersect AC and AB at Q and R respectively. Prove that RQ || BC.

Solution:

Given:

In ΔABC, P is a point on the median AD. Extended BP and CP intersect AC and AB at Q and R respectively.

Let P be a point on the median AD of the ΔABC.

Extended BP and CP intersect AC and AB at the points Q and R respectively.

To prove RQ || BC.

Construction: Let us extend PD to T in such a way that PD = DT.

Let us join B, T, and C, T.

Proof: In the quadrilateral BPCT, BC and PT are two diagonals. Also, BD = CD.

[because AD is the median] and PD = DT [by construction]

i..e, the diagonals of the quadrilateral BPCT bisect each other.

∴ BPCT is a parallelogram.

∴ BP || TC and TB || CP.

Now, in ΔABT, RP || BT [because TB || CP]

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AR}}{\mathrm{BR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{TP}}\) ……(1)

Again, in ΔACT, QP || CT [because BP || TC]

∴ by Thales’theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{TP}}\)…….(2)

Then from (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AR}}{\mathrm{BR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

∴ in ΔABC, \(\frac{\mathrm{AR}}{\mathrm{BR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

∴ by the converse of Thales’ theorem, RQ || BC.

Hence RQ || BC (proved)

“Step-by-step solutions for similarity problems Class 10”

Example 5. The two medians BE and CF of AABC intersect each other at the point G and if the line segment FE intersects the line segment AG at the point O, then prove that AO = 30G.

Solution:

Given:

The two medians BE and CF of AABC intersect each other at the point G and if the line segment FE intersects the line segment AG at the point O

In ΔABC, BE and CF medians of ΔABC intersect each other at G.

FE intersects AG at point O.

To prove: AO = 3OG.

Construction: Let us extend AG.

Also, let extended AG intersects BC at D.

Then G is centroid of ΔABC and AD is its median [because the medians of any triangle are concurrent.]

Proof: G is the centroid of ΔABC and AD is its median.

AG: GD = 2:1 [since the centroid of the triangle divides the medians in the ratio 2:1]

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AG}}{\mathrm{GD}}=\frac{2}{1}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AO}+\mathrm{OG}}{\mathrm{OD}-\mathrm{OG}}=\frac{2}{1}\)

or, 2OD – 2OG = AO + OG

or, 2OD – AO = OG + 2OG

or, 2 AO – AO = 3OG

Hence AO = 3OG (proved)

[because in ΔABD, FO || BD, line segment joining the midpoints of any two sides of a traiangle is parallel to its third side.

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AF}}{\mathrm{BF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AO}}{\mathrm{OD}}\) or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AF}}{\mathrm{AF}}\)=\(\frac{\mathrm{AO}}{\mathrm{OD}}\) (because AF = BF)

or, 1 = \(\frac{\mathrm{AO}}{\mathrm{OD}}\) or, OD = AO.]

AO = 30G

Example 6. Prove that the line segment joining the mid-point of two transverse sides of a trapezium is parallel to its parallel sides.

Solution:

Let ABCD be a trapezium of which AD || BC.

AB and DC are two of its transverse sides, the midpoints of which are E and F respectively.

To prove EF || AD and EF || BC.

Construction: Let us extend BA and CD.

Also, let extended BA and CD intersect each other at point P.

Proof: In ΔPCB, AD || BC,

∴ by Thales’ theorem.

\(\frac{P A}{A B}=\frac{P D}{D C} \text { or, } \frac{P A}{2 A E}=\frac{P D}{2 D F}\)

[because E and F are the midpoints of AB and DC respectively.]

or, \(\frac{P A}{A E}=\frac{P D}{D F}\)

∴ in ΔPEF, \(\frac{P A}{A E}=\frac{P D}{D F}\)

∴ by the converse of Thales’ theorem, AD || EF.

Again, ∵ AD || BC, ∴AD || EF || BC. (Proved)

Example 7. D is any point on the side BC of ΔABC. P and Q are centroids of ΔABD and ΔADC respectively. Prove that PQ || BC.

Solution:

Given:

D is any point on the side BC of ΔABC. P and Q are centroids of ΔABD and ΔADC respectively.

Let D is any point on the side BC of ΔABC.

The medians BE and DF of ΔABD intersect each other at P and two medians CE and DS of ΔACD intersect each other at Q.

∴ P and Q are two centroids of ΔABD and ΔADC respectively.

Let us join P and Q.

To prove: PQ || BC

Proof: P is the centroid of ΔABD.

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{BP}}{\mathrm{PE}}=\frac{2}{1}\) [∵ centroid divides internally each median in the ratio 2:1]

or, BP = 2PE………..(1)

Similarly, CQ = 2QE……….(2)

Now, in ΔEBC, \(\frac{\mathrm{EP}}{\mathrm{BP}}=\frac{\mathrm{EP}}{2 \mathrm{EP}}=\frac{1}{2}\) [from(1)]…….(3)

Again, in ΔEBC, \(\frac{\mathrm{EQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{EQ}}{2 \mathrm{EQ}}=\frac{1}{2}\) [from(2)]…….(4)

∴ from (3) and (4) we get, \(\frac{E P}{B P}=\frac{E Q}{C Q}\)

i.e., in ΔEBC the straight line segment PQ has divided both BE and CE in such a way that \(\frac{E P}{B P}=\frac{E Q}{C Q}\)

∴ by the converse of Thales’ theorem we get, PQ || BC.

Hence PQ || BC. (Proved)

“WBBSE Mensuration Chapter 5 practice questions on similarity”

Example 8. Two triangles ΔPQR and ΔSQR are drawn on the same base QR and on the same side of QR and their areas are equal. If F and G are two centroids of two triangles, then prove that FG || QR.

Solution:

Given:

Two triangles ΔPQR and ΔSQR are drawn on the same base QR and on the same side of QR and their areas are equal. If F and G are two centroids of two triangles,

Let ΔPQR and ΔSQR have the same base QR and lie on the same side of QR so that the areas are equal.

F and G are the centroids of ΔPQR and ΔSQR respectively.

Let us join F, G.

To prove FG || QR.

Construction: Let T is the midpoint of QR.

∴ F must lie on the median PT of ΔPQR. Let us join P, T.

Similarly, G must lie on the median ST of ΔSQR. Let us join S, T.

Proof: F is the centroid of ΔPQR and PT is one of its medians,

∴ PF : FT = 2: 1 [∵ the centroid ofa triangle divides its median at the ratio 2:1]

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{PF}}{\mathrm{FT}}=\frac{2}{1}\) = or, PF = 2 FT …….(1)

Similarly, SG = 2GT…….(2)

Now, in ΔPST, the line segment FG intersects PT at F and intersect ST at G,

when \(\frac{P F}{F T}=\frac{2 F T}{F T}=2 \text { and } \frac{S G}{G T}=\frac{2 G T}{G T}=2 \text {, i.e., } \frac{P F}{F T}=\frac{S G}{G T}\)

∴ FG || PS……(3)

Again, ΔPQR and ΔSQR lie on the same base QR and they lie on the same side of QR, the areas of the triangles being equal.

∴ they must lie between same parallel couples.

∴ PS || QR ………(4).

Then from (3) and (4) we get, FG || PS || QR.

Hence FG || QR (Proved)

Example 9. Prove that two adjacent angles of any parallel side of an isosceles trapezium are equal.

Solution:

Given: Let ABCD be an isosceles trapezium of which AD = BC, AB || DC, and ∠ADC and ∠BCD are two adjacent angles of its parallel side DC.

To prove ∠ADC = ∠BCD.

Construction: Let us extend BA and CB and let extend DA and extended CB intersect each other at O.

Proof: In AODC, AB || DC (given),

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{OA}}{\mathrm{AD}}=\frac{\mathrm{OB}}{\mathrm{BC}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{OA}}{\mathrm{BC}}=\frac{\mathrm{OB}}{\mathrm{BC}}\) [because AD = BC] or, OA = OB

Now, OD = OA + AD = OB + BC [because OA = OB and AD = BC]

∴ OD = OC, ∴ ∠ODC = ∠OCD or, ∠ADC = ∠BCD.

Hence ∠ADC =∠BCD. (Proved)

Example 10. ΔABC and ΔDBC are situated on the same base BC and on the same side of BC. E is any point on the side of BC. Two line through the point E and parallel to AB and BD intersects the sides AC and DC at the points F and G respectively. Prove that AD || FG.

Solution:

Given:

ΔABC and ΔDBC are situated on the same base BC and on the same side of BC. E is any point on the side of BC. Two line through the point E and parallel to AB and BD intersects the sides AC and DC at the points F and G respectively.

Given: Let ΔABC and ΔDBC have the same base BC and lie on the same side of BC.

E is any point on the side BC.

Two straight line passing through E and parallel to AB and BD intersect AC and DC at the points F and G respectively.

To prove AD || FG.

Proof: In ΔABC, FE || AB.

∴ by Thales’ theorem,

\(\frac{\mathrm{CF}}{\mathrm{FA}}=\frac{\mathrm{CE}}{\mathrm{EB}}\)……. (1)

Similarly in ΔBCD, GE || DB,

∴ By Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{CG}}{\mathrm{GD}}=\frac{\mathrm{CE}}{\mathrm{EB}}\)……(2)

From (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{CF}}{\mathrm{FA}}=\frac{\mathrm{CG}}{\mathrm{GD}}\).

∴ in ΔACD, FG divides AC and DC in such a way that \(\frac{\mathrm{CF}}{\mathrm{FA}}=\frac{\mathrm{CG}}{\mathrm{GD}}\).

∴ By the converse of Thales’ theorem, FG || AD.

Hence AD || FG. (Proved)

Example 11. In a right-angled triangle ∠A is a right-angle and AO is perpendicular to BC at the point O. Prove that AO2 = BO x CO.

Solution:

Given:

In a right-angled triangle ∠A is a right-angle and AO is perpendicular to BC at the point O.

Let in ΔABC, ∠A is a right angle, AO is perpendicular to BC at O.

∴ ∠AOC = 1 right angle.

Now, in ΔAOB and ΔAOC, ΔAOB = ΔAOC [∵ right angle]

∵ ∠BAO = ∠ACO [∵ ∠BAO = ∠BAC – ∠CAO = 90° – ∠CAO = ∠ACO ∵∠AOC = 90°]

∴ ΔAOB and ΔAOC are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AO}}{\mathrm{CO}}=\frac{\mathrm{BO}}{\mathrm{AO}}\)

or, AO2 = BO x CO

Hence AO2 = BO x CO. (proved)

“Examples of similar figures for WBBSE Class 10 Maths”

Example 12. A straight line drawn through D of the parallelogram ABCD intersects AB and the extended part of CB at points E and F respectively. Prove that AD: AE = CF: CD.

Solution:

Given:

A straight line drawn through D of the parallelogram ABCD intersects AB and the extended part of CB at points E and F respectively.

Let the straight line DF drawn through D of the parallelogram ABCD intersect AB and the extended CB at points E and F respectively.

To prove: AD: AE = CF: CD

Proof: In ΔADE and ΔDCF,

∠DAE = ∠DCF [opposite angles of a parallelogram are equal.]

∠ADE = ∠CFD [∵ AD || FC and DF is their transversal, ∠ADE = alternate ∠CFD.]

∴ ΔADE and ΔDCF are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{CF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AE}}{\mathrm{CD}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AE}}=\frac{\mathrm{CF}}{\mathrm{CD}}\)

Hence AD: AE = CF: CD (Proved)

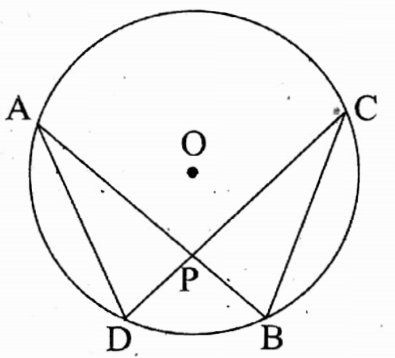

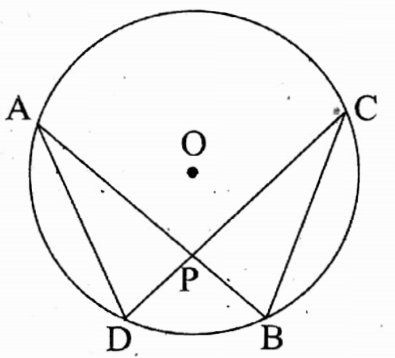

Example 13. Two chords AB and CD of a circle intersect at a internal point P of the circle. Prove that AP x BP = CP x DP.

Solution:

Given:

Two chords AB and CD of a circle intersect at a internal point P of the circle.

Let AB and CD be two chords of a circle with centre at O and they intersect each other at an internal point P of the circle.

To prove: AP x BP = CP x DP.

Construction: Let us join A, D and B, C.

Proof: In ΔAPD and ΔBPC, ∠APD = ∠BPC, [∵ opposite angles]

∠PAD = ∠PCB [∵ two angles in circle produced by the arc BD.]

∴ ΔAPD and ΔBPC are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{CP}}=\frac{\mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{BP}}\)

∴ AP x BP = CP x DP. (Proved)

Example 14. AB is a diameter of a circle. BP is a tangent to the circle at B. A straight line passing through A intersects BP at C and the circle at D. Prove that BC2 = AC x CD.

Solution:

Given:

AB is a diameter of a circle. BP is a tangent to the circle at B. A straight line passing through A intersects BP at C and the circle at D.

Let AB is a diameter of the circle with centre at O.

BP is tangent to the circle at B.

The straight line AC passing through A intersects BP at C and the circle at D.

To prove BC2 = AC x CD.

Construction: Let us join B and D.

Proof: In ΔABD, ∠BAD = 90° – ∠ABD [∵ ∠ADB = semicircular angle = 90°]

= ∠ABC – ∠ABD [∵ BP is a tangent and OB is a radius through point of contact, ∴ ∠ABC = 90°] = ∠DBC

Then in ΔABC and ΔBCD,

∠ABC = ∠BDC [∵ each is a right angle]

∠BAC = ∠BAD = ∠DBC [∵ Proved]

∴ ΔABC and ΔBCD are equiangular

∴ by Thales’theorem we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{CD}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{BC}}\)

or, BC2 = AC x CD .

Hence BC2 = AC x CD (Proved)

Example 15. In the cyclic quadrilateral ABCD, the diagonal BD bisects the diagonal AC. prove that AB x AD = CB x CD

Solution:

Given:

In the cyclic quadrilateral ABCD, the diagonal BD bisects the diagonal AC.

Let ABCD be a cyclic quadrilateral in the circle with centre at O.

The diagonal BD of ABCD intersects the diagonal AC of ABCD at P in such a way that AP = CP.

To prove AB x AD = CB x CD.

Proof: Since diagonal BD bisects the diagonal AC at P, ∴ AP = CP.

Now, in ΔAPB and ΔCPD, ∠APB = ∠CPD [∵ opposite angles]

and ∠BAP = ∠CDP [∵ these are two angles in the circle produced by the chord BC.]

∴ ΔAPB and ΔCPD are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{CD}}{\mathrm{DP}}\)…..(1)

Again, ΔAOD and ΔBOC are equiangular

[∵ ∠APD = opposite ∠BPC and ∠PAD = ∠PBC (same angles in circle)]

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DP}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{CP}}\)

Now, multiplying (1) by (2) we get,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AP}} \times \frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{DP}}=\frac{\mathrm{CD}}{\mathrm{DP}} \times \frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{CP}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB} \times \mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{CD} \times \mathrm{BC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP} \times \mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{DP} \times \mathrm{CP}}=1\)

[∵ AP = CP] or, AB x AD = CD x BC

Hence AB x AD = CB x CD (proved)

Example 16. AD is a diameter of the circumcircle of ΔABC. AE is perpendicular to BC. Prove that AB x AC – AD x AE.

Solution:

Given:

AD is a diameter of the circumcircle of ΔABC. AE is perpendicular to BC.

Let the circle with centre O be the circumcircle of ΔABC.

AD is its diameter. AE ⊥ BC.

To prove AB x AC = AD x AE.

Construction: Let us join C and D.

Proof: in ΔABE and ΔACD,

∠AEB = ∠ACD [∵ AE ⊥ BC and ∠ACD = semicircular angle = 1 right angle]

∠ABE = ∠ADC [∵ ∠ABE and ∠ADC are two angles in circle produced by the arc \(\overparen{A C}\)]

∴ ΔABE and ΔACD are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AC}}\)

∴ AB x AC = AD x AE (proved)

Example 17. XY is a straight line parallel to the side MT of the parallelogram MNOT, which intersects the side MN at X and the side TO at Y. E and F are two points on XY. If ME and TF are extended, they intersect at P and the extended NE and OF intersect each other at Q. Prove that PQ || MN || TO.

Solution:

Given:

XY is a straight line parallel to the side MT of the parallelogram MNOT, which intersects the side MN at X and the side TO at Y. E and F are two points on XY. If ME and TF are extended, they intersect at P and the extended NE and OF intersect each other at Q.

Given: XY is a straight line parallel to the side MT of the parallelogram MNOT, which intersects the side MN at X and the side TO at Y.

E and F are two points on XY.

If ME and TF are extended, they intersect at P and the extended NE and OF intersect each other at Q.

To prove PQ || MN || TO.

Proof: In ΔPMT, EF || MT [∵ XY || MT]

by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{PE}}{\mathrm{ME}}=\frac{\mathrm{PF}}{\mathrm{TF}}=\frac{\mathrm{EF}}{\mathrm{MT}}\)…….(1)

Again, in ΔQON, EF || NO [∵ XY || MT || NO]

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{QE}}{\mathrm{EN}}=\frac{\mathrm{QF}}{F O}=\frac{\mathrm{EF}}{\mathrm{NO}}\)

From (1) and (2) we get,

\(\frac{\mathrm{PE}}{\mathrm{ME}}=\frac{\mathrm{EF}}{\mathrm{MT}}\) and \(\frac{\mathrm{QE}}{\mathrm{EN}}=\frac{\mathrm{EF}}{\mathrm{NO}}\)……..(3)

But ∵ MNOT is a parallelogram, ∴ MT = NO

[∵ Opposite sides of any parallelogram are equal]

From (3) we get, \(\frac{P E}{M E}=\frac{\mathrm{QE}}{\mathrm{EN}}\)

∴ ΔMEN – ΔPEQ, i.e., ∠MNE = ∠PQE,

∠NME = ∠QPM and ∠MNQ = ∠PQN.

But these are alternate angles when PQ and MN are intersected by the transversal NQ.

∴ PQ || MN ………(4)

Again, since MNOT is a parallelogram, ∴MN || TO……(5)

Then from (4) and (5) we get, PQ || MN || TO.

Hence PQ || MN || TO. (Proved)

Example 18. In ΔPQR, ∠Q = 2∠R; The bisector of ∠PQR intersects PR at the point D. Prove that PQ.QR = QD.PR.

Solution:

Given:

In ΔPQR, ∠Q = 2∠R; The bisector of ∠PQR intersects PR at the point D.

In ΔPQR, ∠Q = 2∠R; Bisector QD of ∠PQR intersects PR at D.

To prove: PQ.QR = QD.PR ∠Q = 2∠R (given)

Proof: Since

Again, ∠PQD = ∠DQR [∵ QD is the bisector of ∠PQR]

∴ ∠PQD = ∠DRQ.

Then in ΔPQR and ΔPQD, ∠PRQ = ∠PQD, ∠QPR =∠QPD

∴ ΔPQR and ΔPQD are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{PQ}}{\mathrm{QD}}=\frac{\mathrm{PR}}{\mathrm{QR}}\)

∴ PQ.QR = QD.PR. (Proved)

“WBBSE Class 10 Maths solved problems on similarity”

Example 19. PQ is a diameter of a circle and AB is such a chord of it that it is perpendicular to PQ. If C be the point of intersection of PQ and AB, then prove that PC.QC = AC.BC.

Solution:

Given:

PQ is a diameter of a circle and AB is such a chord of it that it is perpendicular to PQ. If C be the point of intersection of PQ and AB

Let PQ is a diameter of the circle with centre at O.

The chord AB is perpendicular to PQ and has intersected PQ at C.

To prove: PC.QC = AC.BC.

Construction: Let us join B, Q and A, P.

In ΔACP and ΔBCQ, ∠ACP = ∠BCQ [∵ AB ⊥ PQ, each is right-angled.]

and ∠APC = ∠QBC [∵ these are two angles in circle produced by the arc \(\overparen{A Q}\)]

∴ ΔACP ~ ΔBCQ.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{PC}}{\mathrm{BC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{QC}}\)

or, PC.QC = AC.BC

Hence PC. QC = AC. BC (Proved)

Example 20. PQRS is a cyclic quadrilateral. Extended PQ and SR intersect each other at A. Prove that AP.AQ = AR.AS.

Solution:

Given:

PQRS is a cyclic quadrilateral. Extended PQ and SR intersect each other at A.

Let PQRS is a cyclic quadrilateral in the circle with centre at O.

Extended PQ and RS intersect each other at A.

To prove: AP.AQ = AR.AS.

Proof: In ΔAPS and ΔAQR, ∠APS = ∠ARQ and

[∵ ∠QPS + ∠QRS = 180° or, ∠QPS + 180° – ∠QRA = 180° or, ∠QPS = ∠QRA]

∠ASP – ∠AQR [for similar reason]

∴ ΔAPS and ΔAQR are equiangular.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{AR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AS}}{\mathrm{AQ}}\)

or, AP.AQ = AR.AS.

Hence AP AQ = AR.AS (Proved)

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles

In the previous part of this chapter, you have studied about similar triangles, congruent triangles and about their properties and conditions.

In the present part we shall discuss about the relations between the sides of two similar triangles and the theorems related to them.

If we measure the lengths of the sides of two similar triangles and determine their ratios, then we shall see that the corresponding sides of two similar triangles are proportional, i.e., the corresponding sides of two similar triangles are proportional.

We shall now prove this theorem logically with the help of the geometric method.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles Theorems

Theorem 1. If two triangles are similar then prove that their corresponding sides are in same ratio, i.e., their corresponding sides are proportional.

Given: Let ΔABC and ΔDEF are two similar triangles, i.e., ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E and ∠C = ∠F.

To prove \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

Construction: Let us cut off AP and AQ from AB and AC of the ΔABC equal to DE and DF respectively. Let us join P and Q.

Proof: In ΔAPQ and ΔDEF, AP = DE, AQ = DF [by construction] and ∠PAQ = ∠EDF.

∴ ΔAPQ ≅ ΔDEF [by the S-A-S condition of congruency]

∴ ∠APQ = ∠DEF [∵ corresponding angles of congruent triangles.]

or, ∠APQ = ∠ABC [∵ ∠DEF = ∠ABC (given)] ,

But these are similar angles.

∴ PQ || BC.

∴ \(\quad \frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{BP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\) [by Thales’ theorem]

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BP}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{AQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{BP}+\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{CQ}+\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{AQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AQ}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)……(1)

[∵ AP = DE and AQ = DF.]

Similarly, cutting parts from BA and BC respectively equal to DE and EF, it can be prove that

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)……(2)

∴ from (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)= \(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

Hence \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)= \(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\), i.e.,

The corresponding sides of two similar triangles are proportional. (Proved)

Theorem 2. If the sides of two triangles are in same ratio, then their corresponding angles are equal, i.e., two triangles are similar.

Given: Let the sides of the ΔABC and ΔDEF are in same ratio,

i.e., \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)= \(\frac{\mathrm{CA}}{\mathrm{DF}}\),

To prove ΔABC ~ ΔDEF, i.e., ∠A =∠D, ∠B – ∠E and ∠C = ∠F.

Construction: Let the parts AP and AQ are cut offfrom AB and AC in such a way that the two parts are equal to DE and DF respectively.

Let us join P and Q.

Proof: Given that \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{AQ}}\)[∵ DE = AP and DF = AQ by construction]

∴ by the converse of Thales’ theorem, PQ || BC.

∴ ∠B = ∠APQ [∵ similar angles] and ∠C = ∠AQP [∵ similar angles]

∴ ΔABC and ΔAPQ are similar.

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{PQ}}\)…….. (1),

But \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AP}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}\) [∵ AP = DE] = \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)…….(2)

From (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\), ∴ PQ = EF.

Then in ΔAPQ and ΔDEF, AP = DE, AQ = DF and PQ = EF.

∴ ΔAPQ = ΔDEF [by the S-S-S condition of congruency]

∴ ∠APQ = ∠DEF = ∠E corresponding angles of similar triangles]

But ∠APQ = ∠B, ∴ ∠B = ∠E

Again, ∠AQP = ∠DFE = ∠F [for similar reason]

But ∠AQP =∠C, ∴ ∠C = ∠F

It is then obvious that ∠A = ∠D.

i.e, in ΔABC and ΔDEF, ∠A – ∠D, ∠B = ∠E and ∠C = ∠F.

∴ ΔABC ~ ΔDEF. (Proved)

From above discussion we can say that two triangles will be similar if

- Their sides are proportional; or

- Their corresponding angles are equal.

Similarly, if the sides of two polygons be proportional and the corresponding angles are equal, then the polygons are similar.

Again, if any one angle of a triangle be equal to one angle of another triangle and their sides adjacent to that angle be proportional, then the triangles will be similar.

We shall now prove this theorem logically by the method of geometry.

Theorem 3. If in two triangles, an angle of one triangle is equal to the angle of another triangle and the adjacent sides of the angle are proportional, then two triangles are similar.

Given: Let in ΔABC and ΔDEF, ∠A = ∠D and \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

To prove ΔABC ~ ΔDEF.

Construction: Two parts DP and DQ equal to AB and AC are cut off respectively from DE and DF.

Let us join P and Q.

Proof: Given that \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{DP}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{DQ}}{\mathrm{DF}}\) [∵ AB = DP, AC = DQ]

∴ PQ || EF [by the converse of Thales’ theorem]

∴ ∠DPQ = ∠DEF …..(1) [∵ similar angles]

∴ ∠DQP = ∠DFE ……(2) [ similar angles]

Again, ΔDPQ = ΔABC [∴ ∠D = ∠A, DP = AB and DQ = AC]

∴ ∠DPQ = similar ∠B, from (1) we get ∠B = ∠DEF, i.e. ∠B = ∠E.

Again, ∠DQP = similar ∠C, from (2) we get, ∠C = ∠DQP, i.e., ∠C = ∠F.

in ΔABC and ΔDEF, ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E and ∠C = ∠F.

∴ ΔABC ~ ΔDEF. (Proved)

We know that if a perpendicular is drawn from the right angular point of any right-angled triangle to its hypotenuse, then the triangle is divided into two right-angled triangles.

We shall now prove logically that the two right-angled triangle thus produced are similar to each other and each of them is also similar to the original right-angled triangle.

Theorem 4. If any right-angled triangle if a perpendicular is drawn from right angular point on the hypotenuse then prove that the two triangles on both sides of this perpendicular are similar and each of them is similar to original triangle.

Given: Let ΔBC be a right-angled triangle of which A = 90°.

So, the hypotenuse is BC. AD is perpendicular to the hypotenuse BC from the right-angular point A.

Then two right-angled triangles ΔABD and ΔACD have been produced.

To prove

- ΔABD ~ ΔABC

- ΔACD ~ ΔABC; and

- ΔABD ~ ΔACD

Construction: Let us draw a perpendicular AD from the right angular point A to the hypotenuse BC which intersects BC at the point D.

Proof:

1. In ΔABD and ΔABC, ∠ADB = ∠BAC each is right-angle] ∠ABD is common to both the triangles.

Obviously, ∠BAD = ∠ACB [∵ sum of three angles of any triangle is 2 right angles or 180°]

So, in ΔABD and ΔABC, ∠ADB = ∠A, ∠ABD = ∠B and ∠BAD = ∠C.

Hence ΔABD ~ ΔABC [(1)Proved]

2. In ΔACD and ΔABC, ∠ADC = ∠BAC, [∵ each is a right angle.]∠ACD is common to both the triangles.

Obviously, ∠CAD = ∠ABC [∵ sum of three angles of any triangle is 2 right angles or 180°]

So in ΔACD and ΔABC, ∠ADC = ∠A, ∠ACD = ∠C and ∠CAD = ∠B.

Hence ΔACD ~ ΔABC. [(2) Proved]

3. Now, ΔABD and ΔACD, ∠ADB = ∠ADC [∵ each is a right angle]

∴ ∠ABD + ∠BAD = 90° and ∠CAD + ∠ACD = 90°

∴ ∠ABD = 90° – ∠BADor, ∠ABD = ∠CAD [∵ ∠A = 90°]

i.e., in ΔABD and ΔACD, ∠ADB – ∠ADC, ∠ABD = ∠CAD and ∠BAD = ∠ACD, i.e., three angles of each of the triangles are equal.

Hence ΔABD ~ ΔACD [(3) Proved]

Corollary 1. According to theorem 4, ΔABC ~ ΔABD.

∴ \(\frac{B C}{B A}=\frac{B A}{B D}\) = or, BA2 = BC. BD.

∴ BA is the mean-proportional of BC and BD.

Corollary 2. According to the theorem 4, ΔABD ~ ΔACD,

∴ \(\frac{D B}{D A}=\frac{D A}{D C}\) or, DA2 = DB.DC

∴ DA is the mean proportional of DB and DC.

Corollary 3. According to the theorem 4, ΔABC ~ ΔACD,

∴ \(\frac{C B}{C A}=\frac{C A}{C D}\) or.CA2 = CB.CD.

∴ CA is the mean-proportional of CB and CD

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Some Essential Theorems

Theorem 1. (1) Prove that the ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the ratio of the square of the corresponding sides.

Given: Let ΔABC and ΔPQR are two similar triangles.

To prove

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{PQR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}^2}{\mathrm{PQ}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}^2}{\mathrm{QR}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}^2}{\mathrm{PR}^2}\)

Construction: Let us draw a perpendicular AD from A to BC and a perpendicular PM from P to QR.

Proof: ∵ ΔABC ~ ΔPQR,

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}}\)……(1)

Again, ΔABD ~ΔPQM [∵ ∠ADB = ∠PMQ and ∠B = ∠Q]

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{PM}}\)…….(2)

Now, from (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{PM}}\)…….(3)

Then, \(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{PQR}}=\frac{\frac{1}{2} \times \mathrm{BC} \times \mathrm{AD}}{\frac{1}{2} \times \mathrm{QR} \times \mathrm{PM}}\)

[∵ Base = BC and height = AD]

[∵ Base = QR and height = PM]

= \(\frac{\mathrm{BC} \times \mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{QR} \times \mathrm{PM}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}} \times \frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{PM}}\)

= \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}} \times \frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}}\)[from (3)]

= \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}^2}{\mathrm{QR}^2}\)…..(4)

Again, since ΔABC and ΔPQR are similar to each other,

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{QR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{PR}}\)

or,\(\frac{\mathrm{BC}^2}{\mathrm{QR}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}^2}{\mathrm{PQ}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}^2}{\mathrm{PR}^2}\)

Hence from (4) we get,

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{PQR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}^2}{\mathrm{PQ}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}^2}{\mathrm{QR}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}^2}{\mathrm{PR}^2}\) (Proved)

2. The ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the ratio of the squares of their corresponding heights.

Given: Let ΔABC and ΔDEF are two similar triangles, the heights of them are AM and DN respectively.

To prove

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{DEF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AM}^2}{\mathrm{DN}^2}\)

Proof: ΔABC ~ ΔDEF, by theorem 1(1) we get,

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{DEF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}^2}{\mathrm{DE}^2}\)……(1)

Again, in ΔABM and ΔDEN, ∠AMB = ∠DNE [∵ each is a right angle] and ∠ABM = ∠DEN (given)

∴ ΔABM ~ ΔDEN

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{AM}}{\mathrm{DN}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}^2}{\mathrm{DE}^2}=\frac{\mathrm{AM}^2}{\mathrm{DN}^2}\)

From (1) we get,

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{DEF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AM}^2}{\mathrm{DN}^2}\) (Proved)

3. Prove that the ratio of the areas of two similar triangles is equal to the ratio of the squares of their corresponding medians.

Given: Let ΔABC and ΔPQR be two similar triangles of which AD and PM are two corresponding medians.

To prove

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{PQR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}^2}{\mathrm{PM}^2}\)

Proof: ΔABC ~ ΔPQR,

∴ by theorem 4 (1), \(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{PQR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}^2}{\mathrm{PQ}^2}\)….(1)

Again, ∵ ΔABC ∼ ΔPQR,

∴ \(\frac{A B}{P Q}=\frac{B C}{Q R}=\frac{A C}{P R}\)….(2)

From (2) we get, \(\frac{A B}{P Q}=\frac{B C}{Q R}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{2 \mathrm{BD}}{2 \mathrm{QM}}=\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{QM}}\)…….(3)

Again in ΔABD and ΔPQM, ∠ABD = ∠PQM [∵ ΔABC ~ ΔPQR.]

and \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{PQ}}=\frac{2 \mathrm{BD}}{2 \mathrm{QM}}\) [from (3)]

∴ ΔABD ∼ ΔPQM

∴ \(\frac{A B}{P Q}=\frac{B D}{Q M}=\frac{A D}{P M}\) [by Thales’ theorem]

∴ from (1) we get,

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{PQR}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}^2}{\mathrm{PM}^2}\)(proved)

4. The ratio of the areas of two triangles having same heights will be equal to the ratio of their corresponding bases.

Given: Let the heights of ΔABC and ΔDEF be each h units.

BC and EF are the two corresponding bases of them.

To prove

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{DEF}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)

Proof: We know, area of a triangle = \(\frac{1}{2}\) x Base x Height

∴ area of ΔABC = \(\frac{1}{2}\) x BC x h…..(1)

area of ΔDEF =\(\frac{1}{2}\) x EF x h……. (2)

Now, dividing (1) by (2) we get

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{DEF}}=\frac{\frac{1}{2} \times \mathrm{BC} \times h}{\frac{1}{2} \times \mathrm{EF} \times h}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)

Hence \(\frac{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{DEF}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\) (Proved)

In the following examples how the above theorems are applied in real problems have been discussed thoroughly.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles Multiple Choice Questions

Example 1. In ΔABC and ΔDEF if \(\frac{A B}{D E}=\frac{B C}{D F}=\frac{A C}{E F}\) then

- ∠B = ∠E

- ∠A = ∠D

- ∠B = ∠D

- ∠A = ∠F

Solution: ∵ in ΔABC and ΔDEF, \(\frac{A B}{D E}=\frac{B C}{D F}=\frac{A C}{E F}\)

ΔABC ~ ΔDEF and the corresponding sides of the sides AB, BC and AG are respectively DE, FD and EF.

∴ ∠B = ∠D

∴ 3. ∠B = ∠D is correct.

Example 2. If in ΔDEF and ΔPQR, ∠D = ∠Q and ∠E = ∠R , then which one of the following is not correct?

- \(\frac{E F}{P R}=\frac{D F}{P Q}\)

- \(\frac{Q R}{P Q}=\frac{E F}{D F}\)

- \(\frac{D E}{Q R}=\frac{D F}{P Q}\)

- \(\frac{E F}{R P}=\frac{D E}{Q R}\)

Solution: ∵ in ΔDEF and ΔPQR, ∠D = ∠Q and ∠E = ∠R, ∴ ΔDEF ~ ΔPQR.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, the ratios of the corresponding sides of ΔDEF and ΔPQR are equal.

∴ \(\frac{E F}{P R}=\frac{D F}{P Q}=\frac{D E}{Q R}\)

∴ 2. \(\frac{Q R}{P Q}=\frac{E F}{D F}\) is not correct

Example 3. In ΔABC and ΔDEF, ∠A = ∠E = 40°, AB: ED = AC: EF and∠F = 65°, then the value of ∠B is

- 35°

- 65°

- 75°

- 85°

Solution: In ΔABC and ΔDEF, ∠A = ∠E, AB : ED = AC : EF

∴ ΔABC ~ ΔDEF

∴ ∠A = ∠E, ∠B = ∠D, ∠C = ∠F

∴ in ΔABC, ∠A = 40° [∵ ∠A = ∠E = 40°] and ∠C = 65° [∵ ∠C = ∠F = 65°]

∴ ∠B =180° – (∠A + ∠C) = 180° – (40° + 65°) = 180° – 105° = 75°

∴ 3. 75° is correct.

Example 4. In ΔABC and ΔPQR, if \(\frac{A B}{Q R}=\frac{B C}{P R}=\frac{C A}{P Q}\) then

- ∠A = ∠Q

- ∠A = ∠P

- ∠A = ∠R

- ∠B = ∠Q

Solution: ∵ in ΔABC and ΔPQR,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{QR}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{PR}}=\frac{\mathrm{CA}}{\mathrm{PQ}}\),

∴ ΔABC ∼ ΔPQR

∴ ∠A = ∠Q; ∠B = ∠R, ∠C = ∠P

∴ 1. ∠A = ∠Q is correct.

Example 5. In ΔABC, AB = 9 cm, BC = 6 cm and CA = 7.5 cm. In ΔDEF, the corresponding side of BC is EF; EF = 8 cm and if ΔDEF ~ ΔABC, then the perimeter of ΔDEF will be

- 22.5 cm

- 25 cm

- 27 cm

- 30 cm

Solution:

Given

In ΔABC, AB = 9 cm, BC = 6 cm and CA = 7.5 cm. In ΔDEF, the corresponding side of BC is EF; EF = 8 cm and if ΔDEF ~ ΔAB

∵ ΔADEF ~ ΔABC and the corresponding side of BC is EF,

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}\) = \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

Now, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}\)

or, \(\frac{9 \mathrm{~cm}}{\mathrm{DE}}\) = \(\frac{6 \mathrm{~cm}}{8 \mathrm{~cm}}\)

[∵ AB = 9 cm, BC = 6 cm and EF = 8 cm]

or, DE = 12 cm

Again, \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

or, \(\frac{6 \mathrm{~cm}}{8 \mathrm{~cm}}=\frac{7 \cdot 5 \mathrm{~cm}}{\mathrm{DF}}\)

[∵ AC = 7.5 cm] or, DF = 10 cm

∴ Perimeter of ΔDEF = DE + EF + FD = (12 + 8 + 10) cm = 30 cm

Hence the required perimeter of ΔDEF = 30 cm

∴ 4. 30 cm is correct.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles True Or False

Example 1. If the corresponding angles of two quadrilaterals are equal, then they are similar.

Solution: False

Since here though the angles are equal, their shapes may not be equal, such as four angles of a rectangle and of a square are equal (each is a right angle), but their shapes are not the same.

Example 2. In the adjoining, if ∠ADE = ∠ACB, then ΔADE ~ ΔACB.

Solution: True

Since in ΔADE and ΔABC, ∠ADE = ∠ACB (given) and ∠DAE = ∠BAC, i.e. ∠A is common to both.

∴ ΔADE ~ ΔABC.

Example 3. In ΔPQR, D is a point on the side QR so that PD ⊥ QR; So ΔPQD ~ ΔRPD.

Solution: False

Since here in ΔPQD and ΔRPD, only ∠PDQ = ∠PDR (each is. a right angle),

The other two angles are not equal.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles Fill In The Blanks

Example 1. Two triangles are similar if their _________ sides are proportional.

Solution: corresponding

Example 2. The perimeters of ΔABC and ΔDEF are 30 cm and 18 cm respectively. ΔABC ~ ΔDEF; BC and EF are corresponding sides. If BC = 9 cm, the EF = ______ cm.

Solution: 5-4 cm since ΔABC ~ ΔDEF,

\(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{DE}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AC}}{\mathrm{DF}}=\frac{\mathrm{AB}+\mathrm{BC}+\mathrm{CA}}{\mathrm{DE}+\mathrm{EF}+\mathrm{FD}}=\frac{30 \mathrm{~cm}}{18 \mathrm{~cm}}=\frac{15}{9}\)

\(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{EF}}=\frac{15}{9} \text { or }, \frac{9 \mathrm{~cm}}{\mathrm{EF}}=\frac{15}{9}\)

or, 15 EF =9 x 9 cm

or, EF = \(\frac{9 \times 9}{15} \mathrm{~cm}\)

EF= \(\frac{81}{15}\) =5.4 cm

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles Short Answer Type Questions

Example 1. In the following if ∠ACB = ∠BAD, AC = 8 cm, AB = 16 cm and AD = 3 cm, then find the length of BD.

Solution:

Given:

In the following if ∠ACB = ∠BAD, AC = 8 cm, AB = 16 cm and AD = 3 cm

In ΔABC and ΔABD, ∠ACB = ∠BAD, ∠ABC = ∠ABD,

∴ ΔABC ~ ΔABD.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{AB}}=\frac{\mathrm{CA}}{\mathrm{AD}}\)

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{\mathrm{CA}}{\mathrm{AD}}\) or, \(\frac{16 \mathrm{~cm}}{\mathrm{BD}}=\frac{8 \mathrm{~cm}}{3 \mathrm{~cm}}\)

[∵ AB = 16cm, AC = 8 cm, AD = 3 cm]

or, 8BD = 48 or, BD = \(\frac{48}{8}\) = 6.

Hence the length of BD = 6 cm.

Example 2. In the adjoining, ∠ABC = 90° and BD ⊥ AC. If AB = 5.7 cm, BD = 3.8 cm, CD =5.4 cm, then find the length of BC.

Solution:

Given:

In the adjoining, ∠ABC = 90° and BD ⊥ AC. If AB = 5.7 cm, BD = 3.8 cm, CD =5.4 cm

∵ ∠ABC = 90° and BD ⊥ AC,

∴ ΔABD ~ ΔBCD and ΔABD ~ ΔABC, ΔBCD ~ ΔABC.

Then ΔABC ~ ΔBCD implies = \(\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{B C}{C D}\)

or, \(\frac{5 \cdot 7 \mathrm{~cm}}{3 \cdot 8 \mathrm{~cm}}\) = \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{5.4 \mathrm{~cm}}\)

[∵ AB = 57 cm, BD = 38 cm, CD = 54 cm.]

or, 38 BC = 5.7 x 5.4 or, BC = \(\frac{5.7 \times 5.4}{3.8}\) = 8.1.

Hence the length of BC = 8.1 cm.

Example 3. In beside, ∠ABC = 90° and BD ⊥ AC. If BD = 8 cm and AD = 4 cm, then find the length of CD.

Solution:

Given:

In beside, ∠ABC = 90° and BD ⊥ AC. If BD = 8 cm and AD = 4 cm,

∵ ∠ABC = 90° and BD ⊥ AC,

∴ ΔABD ∼ ΔBCD

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{A D}{B D}=\frac{B D}{C D}\)

∴ from (1) we get, BD2 = AD x CD or, (8)2 = 4 x CD

or, 64 = 4CD or CD = \(\frac{64}{4}\) = 16.

Hence the length of CD = 16 cm.

“Applications of similarity in Class 10 Maths”

Example 4. In trapezium ABCD, BC || AD and AD = 4 cm. The two diagonals AC and BD intersect at the point O in such a way that \(\frac{A O}{O C}=\frac{D O}{O B}=\frac{1}{2}\) Find the length of BC.

Solution:

Given:

In trapezium ABCD, BC || AD and AD = 4 cm. The two diagonals AC and BD intersect at the point O in such a way that \(\frac{A O}{O C}=\frac{D O}{O B}=\frac{1}{2}\)

ΔAOD ∼ ΔBOC,

∴ \(\frac{A O}{O C}=\frac{D O}{O B}=\frac{A D}{B C}\)

or, \(\frac{A D}{B C}=\frac{1}{2}\) [∵\(\frac{A O}{O C}=\frac{D O}{O B}=\frac{1}{2}\)]

or, \(\frac{4}{B C}=\frac{1}{2}\) or, BC = 8

Hence the length of BC = 8 cm.

Example 5. ΔABC ∼ ΔDEF and in ΔABC and ΔDEF, the corresponding sides of AB, BC and CA are DE, EF and DF respectively. If ∠A = 47° and ∠E = 83°, then find the value of ∠C.

Solution:

Given

ΔABC ∼ ΔDEF and in ΔABC and ΔDEF, the corresponding sides of AB, BC and CA are DE, EF and DF respectively. If ∠A = 47° and ∠E = 83°

ΔABC ~ ΔDEF,

∴ ∠A = ∠D, ∠B = ∠E, ∠C = ∠F

∴ ∠D = 47°, ∠E = 83° (given)

∴ ∠F = 180° – (∠D + ∠E)

= 180° – (47° + 83°) = 180° – 130° = 50°

∴ ∠C = 50° [∵ ∠F = ∠C]

Hence the value of ∠C = 50°.

Solid Geometry Chapter 5 Similarity

Relation Between The Sides Of Two Similar Triangles Long Answer Type Questions

Example 1. ABC is a right angled triangle whose ∠B is right angle and BD ⊥ AC; if AD = 4 cm and CD = 16 cm, then calculate the length of BD and AB.

Solution:

Given:

ABC is a right angled triangle whose ∠B is right angle and BD ⊥ AC; if AD = 4 cm and CD = 16 cm,

∵ in ΔABC, ∠B = right angle and BD ⊥ AC.

∴ ΔABC ~ ΔABD

ΔABC ~ ΔBCD

ΔABD ~ ΔBCD

Now, ΔABD ~ ΔBCD implies \(\frac{A D}{B D}=\frac{B D}{C D}\)…..(1)

or, AD x CD = BD2 or BD2 = AD x CD = 4 x 16 = 64

∴ BD = √64 = 8. ∴ BD = 8 cm

Now, AB = vAD2 +BD2 = v42 +82 cm = √80cm \(\sqrt{\mathrm{AD}^2+\mathrm{BD}^2}=\sqrt{4^2+8^2}\)=4√5cm

Hence the length of BD = 8 cm and AB = 4√5 cm

Example 2. AB is a diameter of a circle with centre O, P is any point on the circle, the tangent drawn through the point P intersects the two tangents drawn through the points A and B at the points Q and R respectively. If the radius of the circle be r, then prove that PQ.PR = r2.

Solution:

Given:

AB is a diameter of a circle with centre O, P is any point on the circle, the tangent drawn through the point P intersects the two tangents drawn through the points A and B at the points Q and R respectively.

Let AB is a diameter of the circle with centre at O.

P is any point on the circle. AE and BF are two tangents drawn through A and B which intersect the tangent ST drawn at P at the points Q and R respectively.

To prove PQ.PR = r2 (where r = radius of the circle)

Construction: Let us join O, Q and O, R.

Proof: ∵ the lengths of the tangents to a circle drawn from an external point of the circle are equal and they subtend equal angles at the centre,

∴ QA = QP, PR = BR and ∠AOQ = ∠POQ, ∠BOR = ∠POR

∴ ∠AOQ = ∠POQ = \(\frac{1}{2}\) ∠AOP and ∠BOR = ∠POR = \(\frac{1}{2}\) ∠BOP.

∴ ∠QOR = ∠POQ + ∠POR = \(\frac{1}{2}\) ∠AOP + \(\frac{1}{2}\) ∠BOP = \(\frac{1}{2}\) (∠AOP + ∠BOP)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\) x ∠AOB = \(\frac{1}{2}\) x 180° =90° [∵ ∠AOB = 1 straight angle = 180°]

Again, OP ⊥ QR [∵ OP is a radius passing through the point of contact.]

∴ ΔPOQ ~ ΔPOR. PQ OP

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{P Q}{O P}=\frac{O P}{P R}\) or, PQ.PR = OP2

or, PQ.PR = r2 [∵ OP = r = radius of the circle]

Hence PQ.PR = r2 (Proved)

Example 3. Modhurima have drawn a semicircle with a diameter AB. A perpendicular is drawn on AB from any point C on AB which intersects the semicircle at the point D. Prove that CD is a mean- proportion of AC and BC.

Solution:

Given:

Modhurima have drawn a semicircle with a diameter AB. A perpendicular is drawn on AB from any point C on AB which intersects the semicircle at the point D.

Let ADB is a semicircle with centre at O, of which AB is a diameter. A perpendicular CD is drawn at C on AB which intersects the semicircle at D.

To prove: CD is a mean-proportion of AC and BC, i.e., AC x BC = CD2.

Construction: Let us join A, D and B, D.

Proof: ∵ ADB is a semicircle, ∠ADB is a semicircular angle.

∴ ∠ADB = 1 right angle.

Again, CD is the perpendicular drawn from the right angular point D on the hypotenuse AB.

\(\frac{AC}{CD}=\frac{CD}{BC}\) = or AC x BC = CD2.

Hence CD is a mean proportion of AC and BC. (Proved).

Example 4.In right angled triangle ABC, ∠A is a right angle. AD is perpendicular on the hypotenuse BC. prove that \(\frac{\triangle A B C}{\triangle A C D}=\frac{B C^2}{A C^2}\)

Solution:

Given:

In right angled triangle ABC, ∠A is a right angle. AD is perpendicular on the hypotenuse BC.

In ΔABC, ∠A = right angle.

AD is the perpendicular drawn from the right angular point A to the hypotenuse BC.

∴ ΔABC ~ ΔACD.

\(\frac{\text { Area of } \triangle \mathrm{ABC}}{\text { Area of } \Delta \mathrm{ACD}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}^2}{\mathrm{AC}^2}\)

[∵ BC and AC are corresponding sides]

Hence \(\frac{\Delta \mathrm{ABC}}{\Delta \mathrm{ACD}}=\frac{\mathrm{BC}^2}{\mathrm{AC}^2}\) (proved)

Example 5. AB is a diameter of a circle with centre O. A line drawn through the point A intersects the circle at the point C and the tangent through B at the point D. Prove that

- BD2 = AD.DC

- The area of the rectangle formed by AC and AD for any straight line is always equal.

Solution:

Given:

AB is a diameter of a circle with centre O. A line drawn through the point A intersects the circle at the point C and the tangent through B at the point D.

Let AB be a diameter of the circle with centre at O. A straight line drawn through A y intersects the circle at C and the tangent BT drawn at B at the point D.

To prove TBD2 = AD

- DC.

- The area of the rectangle formed by. AC and AD for any straight line is always equal.

Construction: Let us join B, C

Proof:

1. In ΔABD and ΔBCD, ∠ABD = ∠BCD [∵ BT is a tangent at B and AB is a radius through point of contact,

∴ ∠ABD = 1 right angle; Again, ∠ACB is a semicircular angle. ∴ ∠ACB = 1 right angle.]

Now, ∠BDC = 90° – ∠DBC [∵ ∠BCD =1 right angle]

= ∠ABC [∵ ∠ABD = 1 right angle]

∴ ΔABD ~ ΔBCD.

∴ by Thales’ theorem \(\frac{\mathrm{BD}}{\mathrm{DC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{BD}}\)

∴ BD2 = AD x DC. (Proved).

2. Again, in ΔABD and ΔABC, ∠ABD = ∠ACB [∵ each is a right angle]

∠ADB = 90° – ∠DBC = ∠ABC

∴ ΔABD-ΔABC

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{AC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AD}}{\mathrm{AB}}\) [by Thals’s theorem] or, AB2 = AC x AD

or, (constant)2 = AC x AD [∵ the value of diameter AB is constant]

∴ AC x AD = constant

∴ The area of the rectangle formed by AC and AD for any straight line is always equal. (Proved)

Example 6. The length of the shadow of a stick of length 6 cm is 4 cm. At the same time, if the length of the shadow of a tower be 28 metres, then find the height of the tower.

Solution:

Given:

The length of the shadow of a stick of length 6 cm is 4 cm. At the same time, if the length of the shadow of a tower be 28 metres,

Let CP be the length of the shadow of the stick CD of length 6 cm. CP = 4 cm.

At the same time, AP is the length of the shadow of the tower AB.

As per question, AP = 28 cm

We have to find the height of the tower AB.

Now, in ΔAPB and ΔCPD, ∠PAB = ∠PCD [∵ each is perpendicular to the base, right angles.]

∠P is common to both the triangles,

∴ ΔAPB ~ ΔPCD

Hence by Thales theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{\mathrm{CD}}\) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{CP}}\)

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{AB}}{6 \mathrm{~cm}}=\frac{28 \mathrm{metres}}{4 \mathrm{~cm}}\)

or, AB= \(\frac{2800 \mathrm{~cm} \times 6 \mathrm{~cm}}{4 \mathrm{~cm}}\) =4200 cm=42

Hence the height of the tower is 42 metres.

Example 7. Prove by the theorem of Thales that the third side of a triangle is parallel to the line segment obtained by joining the mid-points of any two sides of the triangle and is half in length of its third side.

Solution: Let P and Q be the mid-points of the two sides AB and AC of the ΔABC.

Let us join P and Q.

Proof: P and Q are the mid-points of AB and AC respectively.

∴ AP = BP and AQ = CQ.

\(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{BP}}=\frac{\mathrm{BP}}{\mathrm{BP}}=1\) and \(\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}=\frac{\mathrm{CQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}=1\)

Then, \(\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{BP}}\) = \(\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{CQ}}\)

∴ by the conversed theorem of Thales’ theorem, PQ || BC. (Proved)

Again in ΔAPQ and ΔABC,

∠APQ = ∠ABC [∵ similar angles]

∠AQP = ∠ACB [∵ similar angles]

and ∠A is common to both the triangles ΔAPQ ~ ΔABC.

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{\mathrm{PQ}}{\mathrm{BC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{AB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{\mathrm{AC}}\)

∴ \(\frac{\mathrm{PQ}}{\mathrm{BC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{AB}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{2AP}}\)

[∵ P is the mid-point of AB, ∴ AB = 2AP.]

or, \(\frac{\mathrm{PQ}}{\mathrm{BC}}=\frac{\mathrm{AP}}{\mathrm{2 AP}}=\frac{1}{2}\)

or, PQ = \(\frac{1}{2}\) BC

Hence PQ || BC and PQ = \(\frac{1}{2}\) BC (proved)

Example 8. Two parallel straight lines intersect three concurrent straight lines at the points A, B, C and X, Y, Z respectively. Prove that AB : BC = XY : YZ.

Solution:

Given:

Two parallel straight lines intersect three concurrent straight lines at the points A, B, C and X, Y, Z respectively.

Let two parallel straight lines CD and EF intersects three straight lines P1Q1, P2Q2, P3Q3concurrent at O at the points A, B, C and X, Y, Z respectively.

To prove AB : BC = XY : YZ.

Proof: In ΔAOB and ΔXOY, ∠OAB = alternate ∠OXY, [CD || EF and P1Q1 is their transversal]

∠OBA = ∠OYX (for similar reason)

∴ ΔAOB ~ ΔXOY

∴ by Thales’ theorem, \(\frac{A B}{X Y}=\frac{O B}{O Y}\)……..(1)

Again, in ΔBOC and ΔYOZ, ∠OBC = alternate ∠OYZ,

[∵ CD || EF and P2O2, is their transversal]

∠BOC = ∠YOZ [∵ opposite angles] ΔBOC ~ ΔYOZ

∴ by Thales’ theorem \(\frac{\mathrm{BC}}{\mathrm{YZ}}=\frac{\mathrm{OB}}{\mathrm{OY}}\)……..(2)

∴ From (1) and (2) we get, \(\frac{A B}{X Y}\)=\(\frac{B C}{Y Z}\)